Watch the full interview below or listen to the full episode on your iPhone HERE.

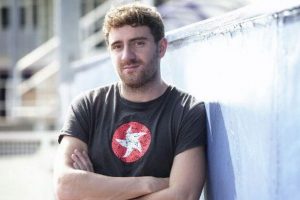

Stu: This week we welcome Andrew Steele to the show. Andrew is a former Olympian and professional athlete. As head of product and professional sport at DNAFit, he shows people how to use their genetic information to get the best results from their diet and training. In this episode we discuss the process, the results and the benefits that can be achieved through testing, enjoy 🙂

Audio Version

- Why is understanding our DNA important?

- How can understanding our DNA help us with our sleep quality?

- I’ve heard a lot about the MTHFR gene, what is its role in the body?

Get More of Andrew Steele

http://dnafit.com/If you enjoyed this, then we think you’ll enjoy this interview:

- Chris Kresser: The ABC of Functional Medicine

- Preventing Dementia, Alzheimer’s & Optimising Brain Function with Dr John Hart

- Dr. Tom O’Bryan – The Autoimmune Fix

Full Transcript

Stu

00:03 Hey this is Stu from 180 Nutrition, and welcome to another episode of the health sessions. It’s here that we connect with the world’s best experts in health, wellness, and human performance, in an attempt to cut through the confusion around what it actually takes to achieve a long lasting health. Now I’m sure that’s something that we all strive to have. I certainly do.

00:23 Before we get into the show you might not know that we make products too, that’s right, we’re into whole food nutrition, and have a range of super foods and natural supplements to help support your day. If you are curious, want to find out more, just jump over to our website. That is 180nutrition.com.au and take a look.

Stu

00:41 Okay, back to the show. This week I’m excited to welcome Andrew Steele. Andrew is a former Olympian and now head of product at DNAFit, an award-winning personalized health and well being company. They help people like you and me to better understand our DNA in order to get the most out of nutrition, fitness, and general well-being.

01:02 In this interview we discuss how we can benefit from this technology, the most common things that people change after testing, and also what the future holds for DNA testing itself. I’m really excited about this technology as it offers the advice that has the potential for us to make better choices all around, which is fantastic. Anyway, enough from me, over to Andrew.

01:27 Hey guys, this is Stu from 180 Nutrition, and I’m delighted to welcome Andrew Steele to the show. Andrew, how are you?

Andrew

01:34 I’m good, thanks. Thanks for having me.

Stu

01:35 No mate. Thank you for your time. Before we get into the questions, as well for our listeners that may not be familiar with you or your work, could you just tell us a little bit about yourself, and who you are, and what you do?

Andrew

01:50 Sure, I’m Andrew. I’m in my current role as the head of products at a company called DNAFit. We specialize in looking at the genetic factors behind fitness and exercise response. We allow people via a home DNA test to personalize their diet, personalize their exercise workout, based on not just their own choices and goals, but also by understanding more about they’re made from a genetic factor.

02:19 Then that plays very well into my previous career, if you will, which was I was an Olympic athlete. I ran the 400 meters and the 4×4 Inter-relay for Great Britain. I spent about 12 years competing professionally there and spent a lot of time traveling all over the world and training everywhere. Part of that experience is what led me to discover the role of light DNA and genetics in sport, basically, and that led me to part of this company.

Stu

02:48 Fantastic mate, that’s a great story. I like it. Just intrigued, were you involved in the DNA when you were competing athletically? Was there a cross-over there?

Andrew

03:02 So last couple of years in my career … so realistically my career was kind of over by that point. I was quite old when it comes to elite 400 meter runners. So, that was the end. There’s a cross-over where I was still training in the morning, get to the office by like mid-day, and then do all that. And I definitely, you know we can get more into detail a bit further down the conversation, but I definitely found some benefit in getting the most out of myself as I was approaching old age in athletic terms basically and so I wished I had come across it sooner in my career should we say.

Stu

03:39 Yeah, okay. I’m intrigued. Was there anything that you were doing previously to obtaining this DNA data that perhaps was holding you back from your athletic potential?

Andrew: 03:57 Yeah, so let me tell you a quick story then, sort of a macro view of my career and some of the learnings there. So when we choose to do something, whether that’s to exercise, nutrition, whatever fits in our lifestyle, people build this off like a bunch of evidence sources even subconsciously. So often it’s sort of what your peers do, you know the people that you’re around, what do they eat? Whose the one that’s in shape, what does he do, what does she do? So we tend to follow that. We tend to follow what we read in the media, like is there certain celebrities that do a certain thing? Do we follow them? And everyone’s kind of searching around for what is the right advice?

Andrew

04:39 The funny thing is, even at that the top level of elite sport, for a very niche physical activity and a very narrow demand, people still don’t really know and they still do the same process. So you say, “Hey, what did Usain Bolt do?” Okay maybe I should do that. It goes on and on.To give you an example, the main part of my career let’s say 8 years where I was really messing around at the elite Olympic level. There was four years running up to the Beijing Olympic Games, and four years running up to the London 2012 games, the home Olympic Games.

05:18 Have you ever run a 400 meters?

Stu

05:19 Yes I have.

Andrew

05:20 Have you ever had the misfortune of doing so?

Stu

05:22 Yeah.

Andrew

05:25 What are your impressions of it? Was it easy, was it hard?

Stu

05:31 Not really, because typically I was raised in the UK and we used to do cross country. It was that section of PE, physical education that nobody really enjoys. You go out there, and it’s typically quite cold, and you just got to run for miles through the mud. Then get yourself on a track, and you’ve got to run hell for leather for this 400 meters. You swap in endurance exercise for high intensity stuff, and no I didn’t enjoy it. It wasn’t my thing.

Andrew

06:05 Yeah, no one really has positive stories to tell of the 400 meters [inaudible 00:06:10].

Stu

06:11 That’s right.

Andrew

06:13 Especially the 400. The reason being is it’s a very unique distance to try and train for because it requires all the sprint energy systems, all this power energy systems that the body has. It requires all the endurance energy systems that body has too. It requires at both ends of the spectrum. There’s often been a debate about should you train like an endurance athlete, and do some sprint. Should you train like a sprint athlete and do some endurance? There’s a difference of thought there.

06:47 Generally speaking at the top level, the considered correct advice or the average correct advice, is that you should train like a sprinter first and foremost, and then you should add some speed endurance, some sort of withstanding the discomfort training if you will. That is born out of most of the elite sprinters, they’re mostly extremely good almost world class 200 meter runners who then have a bit more endurance basically.

07:17 If we go back to that, I’m from Manchester in the North of England. Where we’re meant to be sort of salt of the Earth types, and we work hard, have a lot of graft in us. I was training in Manchester with an old school coach, he’d smoke 40 cigarettes a day, and just have us run and run and run. [inaudible

00:07:38]. It was a real old school environment. Actually that was the first half of my career running up toe Beijing that was quite accessible for me. I reached the Beijing Olympic Games at 23 years old. I made the semifinal in the individual event there, and ran under 45 seconds which is quite an important benchmark elite 400 meters.

Andrew

07:59 Then we actually won a medal in the relay. I say actually because it was a funny way we won this medal. We came fourth at the time, behind the Russian team who just last year were retrospectively disqualified as part of this Russian doping scandal that was uncovered. Last year I became an Olympic medalist for a race I ran ten years ago. It took me 9 years to get my Olympic medal. I did get an Olympic medal.

08:28 I was quite successful doing the old fashioned way, the endurance sort of way for 400 meters, and it worked for me. However, you’re always looking to get better. After the Beijing Games we had 4 years until London 2012 which is like the absolute biggest thing. If you had been in the UK during the run up to it, you knew as anyone else who was there for the run up to the Sydney Games. It defines every waking moment for someone that’s involved in sport. For seven years it was like this is all that matters. You’d meet anyone you say I’m an athlete, they’d say “Oh are you going to be at London 2012?” I don’t know yet, they have not picked the team yet, but hopefully so.

09:12 It was quite a big deal. What happened with this four years to go, we sat down for what’s called your performance review. That’s with the head coach, it’s with the people that pay your bills, the federation. It’s with your coach, your physio, everyone’s got a part like a stakeholder in your journey. Basically we said look you need to get about half a second quicker in the next four years. Literally like that amount time, like half a second. Which is really super small in real everyday life, but it’s a lot amount of time in elite sprinting at least.

Andrew

09:49 One of the takeaways was that you’re pretty bad at the start of this race, you’re pretty slow out the blocks. You probably need to get better at that. You can get better at that by training more of the correct way, the modern way, which is the sprint method.

Stu

10:04 Okay.

Andrew

10:05 Everybody else did that. You have some weaknesses in your race you should probably do that too. So I said yeah that’s cool, that’s fine by me. Basically we fast forward four years time, it didn’t work. I went from number one in the UK in 2008 down to number 7 in the UK on the last day before selection for London 2012. They only take the top 6. Instead of getting a half second quicker, I missed out on the home Olympic games, I actually got about a second slower on average. I basically found out the hard way through trial and error that one training method could be more effective for me than another.

10:37 That’s a story people find in everyday health and fitness. You try one thing, it doesn’t work for them, but it does work for their friend etc. I’ve found this out, not long after the dust had settled, after the mourning of not making it to London 2012, like it was like a death in the family almost. It was such a big deal, not to have got there. My entire life had been building up that, and I hadn’t even made it on the team. It was pretty hard to take.

11:04 When the dust had settled I began to reach around, and say what can I learn from this? Okay, I made the decision that I was going to go back to the old way, back to the old school, the endurance method. I started to explore a number of other factors like sports science, sports physiology, and science physiology around why that might have been the case for me. One of those factors I discovered was the role of genetics in training response, exercise response. Simultaneously, in a great serendipitous move within a few weeks a swab arrived with a post from who is our CEO now, Avi. Who was looking to build this company, looking for feedback from sports people, and how they were made genetically. I did this thing, I was so impressed with how the data matched my experience that we kept in touch.

11:55 I’ll tell you one bit of data, not to go into detail, just one bit. There’s a gene called the ACTN3 gene. It’s the most researched gene around exercise response, and especially sprint ability, sprint response, sprint training, etc. With this gene, like every gene, you can have one of three possible genotypes. The genotypes are described by two letters. In ACTN3 gene it’s either you have the CC version, the CT version, or the TT version. You either have two copies of the C, two copes of the T, or one of each. To make it confusing sometimes in the literature they’re called the R and the X version, but we’ll CT here.

Andrew

12:34 Basically every single Olympic sprinter has the same genotype. Around 99%, somewhere between 97 and 99% of Olympic level sprinters have the C version of this gene. They either have CC or CT. I didn’t have it, I was the absolute anomaly. I’m this 1% of Olympic level sprinters that don’t have the C version of ACTN3. To give you an example why that matters, the C version is really good at building or synthesizing fast switch muscle fibers when you give it fast switch muscle increasing exercise. When you give it sprint exercise it’s pretty good at building sprinter’s muscles.

13:14 I didn’t have it, so the way I built sprinter’s muscles had to by default be different. It was an anomaly from the way I was made. If I was in a group of ten sprinters, and we all did short sprints like I changed my training to do, my benefit from those short sprints was by default different to the other nine. I was the anomaly, so therefore it does not change what you can or can’t be. I don’t have this gene, I was an Olympic medalist in the sprint event. It should perhaps influence how we reach that goal, rather than changing the goal.

13:48 It spoke so personally to me, especially some other things around injury risk, recovery speeds, some nutritional factors, that I was just so impressed. We just kept in touch, and from there we started working together and the business grew from a few of us at the time to 45 in the company now, and 120 in the group that now owns us as well. From early small beginnings, we’ve grown this. For me personally it was a really important learning experience as an athlete.

Stu

14:20 Fantastic mate, that’s an awesome story. It reminds me of the movie Rocky 3, where Sylvester Stallone is training against the Russian, Ivan Drago. He’s lifting logs.

Andrew: 14:34 It’s Rocky 4, don’t get the Rocky’s wrong.

Stu: 14:36 Oh my, what have I done? One guy’s hooked up to all the machines and yes it’s like East vs. West it was brilliant.

Andrew

14:45 Rocky goes to the top of mountain, and doesn’t [inaudible 00:14:49]. He’s in like a barn and stuff.

Stu

14:50 Exactly right.

Andrew

14:54 [inaudible 00:14:54]. Even though we’re talking genetic science it was the bond of the crap that worked for me, but it didn’t work for most. That’s the key.

Stu

15:02 Fantastic. The services then offered by DNAfit. Tell me a bit about that, how simple are they, how complex can you go if you want to?

Andrew

15:13 Yeah, so basically the main core product is we look at around 14 or so genetic traits or categories. We look at those specifically only related to fitness and nutrition. General wellbeing, this is really to a direct consumer sense. This is about giving people things which are actionable, so they can learn a bit more about themselves. They can tweak and change certain parts of their lifestyle, their environment, they’re exercise habits to hopefully get the best out of themselves. It’s not about changing everything, this is not sort of talent ID profile. It won’t tell you what you will or won’t be good at. It won’t say this these are things you definitely should eat.

16:00 Or won’t be good at it or I won’t say, “Hey, this is what you definitely should eat or definitely shouldn’t eat.” It will just be that extra layer of data.

Stu

16:07 Got it.

Andrew

16:08 And it’s we’re very good historically at measuring other parts of our, sort of, let’s say our bio profile, right? So we’ll happily measure our steps, we’ll happily measure heart rate, we’ll happily measure our weight, we might do some other things. We might take our blood test, for example, but traditionally for some reason we’ve only ever considered the static part of vast sort of being as an assumption. So, “Yeah, it looks like he needs more of this or yeah, I feel like I’m made to be more this way or crave this food more than the other person.” So all we’re doing basically is shine a light on that static part we’re all built on this interaction between our nature and our nurture, our genetics and our environment.

Stu

16:53 Got It.

Andrew

16:53 So let’s understand more about the genetic part of that equation so you can better personalize the bits that you can control. So we look at, without wanting to reel off a list, in the exercise side, we look at four factors. So your individualized response to training intensity, so whether you might be a higher responder to certain ends of the intensity spectrum and exercise, so high intensity, low intensity, etc. And injury predisposition specifically around that connective tissue injury, so achilles and lower back patellar and rotator cuff, and recovery profile, aerobic or VO2max trainability and then in the nutrition side, sort of three major sections; macro-nutrient response, so looking at response to refined carbs and saturated fats, whether you might need the average or a raised need above the average RDA for a number of vitamins and minerals and then some traits and sensitivity. So your lactose intolerance, predisposition to celiac, alcohol response, and caffeine metabolism as well.

17:55 So we just give these through like, it’s a simple saliva swab. You do the test at home, so you rub it on the inside of your cheek and send it off in the mail. And it takes us around 10 days when we receive the sample at the lab to generate the reports which is delivered through an online portal and mobile app, pdf downloads, and then every user with a health coaching session with one of our dietitians or sports scientists to go through their results in person as well.

Stu

18:22 Wow.

Andrew

18:22 So we’re basically just trying to give people as deepened insight as possible into how they are made when it comes to their individualized response to the most common sort of exercise and nutrition factors basically.

Stu

18:36 Excellent. Wow, that’s a handy piece of kit, isn’t it? Because I had a … must’ve been four years ago. I had a neutral genomic DNA test and a similar thing with a swab or saliva … I can’t even remember what I did at the time, but I remember getting a big pack of information back and it was in-depth and almost rushing.

19:02 There was an overview sheet in there that explained a lot of it, but I thought that the reporting side was a little bit weak from that perspective. But I had a look on your website and it seems like you guys are really dialed into the reporting side and it seems so beautifully presented in that almost this is the type of food that you were really showing if you will.

Andrew

19:27 Yeah. I think it’s about making it super friendly and easily actionable. Right? So you want to break down this barrier of like, “Understanding my DNA could be quite a scary kind of concepts”. Right? And the reason we put so much effort into making this friendly and approachable is that you can’t get engagement when you can’t engage people in making better choices and giving them advice that they can adhere to unless you can make it break down that barrier between a lab test and actually what action is.

The thing I was likening it to is, before wearables were everyday technology that even the average person would wear, right, you could always get pedometers, you could get slow pedometer, you sat on your belt and it had a low LED said how many steps you’ve done, but nobody cares about that. Nobody engaged in that, nobody used it to improve their health because it was an awful experience, right? It’s the technology wasn’t new. It was just someone needed to package it and all except where we’ve done his hair like now like in wearables, there’s some of the most beautiful apps available to see how you’ve gamified this notion of steps, give them a beautiful interface that they want to share, that they want to show off about, that the only stick to, to improve health.

20:43 And the science behind what we do is largely out there. It was just no one had packaged it together, given it sort of a minimum threshold by which you sort of create what is good science or not and no one has really validated it turning that into action points. And so what we did was just take that and also make this so friendly, don’t make this a lab tests. It’s a lab test, but let’s just break out of the lab and turn it into like, “What can I do with this? How am I made, how can I understand myself and what kind of actions can I take?” And I think that’s where we sort of started to see the market grow suddenly was when actually this became understandable.

21:21 There’s also a shocking sort of statistic which is that to do the same genetic Profile that we can do now, say 15 years ago would have cost over $100,000 per person. And also the technology has become so much more approachable too, right?

21:35 So it’s not all just thanks for the lab technology as well but it’s just important that meeting of personal health data that’s in a beautiful, usable fashion with the sort of ongoing advancements in genetic profiling technology so you can do the lab part of it for an affordable price basically.

Stu

21:56 Got it, got it. And a thought just popped into my mind and that was the utilization of these results with your local GP, for instance. So you going in and you’re having some health issues, and you’ve got access to all these cutting edge information which is unique to you only, does the GP consider that or versed in being able to understand what that information means?

Andrew

22:25 Probably it depends on where you are. So what we did is we built what we called kind of like a pro consumer education academy, right? So in the UK here, we’ve probably educated upwards of 700 practitioners, either physical trainers, dieticians or medical doctors on how these results impact, what’s the research behind it, what kind of actions can you recommend off that? And so we have this kind of pro consumer channel that they buy these tests for their clients and they work with them. Generally, you won’t find GPs doing it, of course, depending on the country, if they’re under a nationalized health system, then they’re not going to use sort of third party technologies in that case, but we do work with a lot of medical clinics across the world and they use that.

23:20 Now the question is, we are not under [inaudible 00:23:22] but what we do is very much not medical, so we don’t look at disease risk, we don’t look at anything diagnostic, we only look at that light at the genetic spectrum around nutrition changes, and exercise changes to be better, to improve, to optimize, not to say, “Hey, you’ve got this variant of this gene.” And we actually don’t even test when you have these genes which would increase serious medical risk predispositions and deliberately so. So we stick very much at this wellness end of the genetic spectrum basically.

Stu

23:52 Got it. Got it. And what are the most common things that you find people change after testing?

Andrew

24:00 Mm-mm. So I mean there’s overall very good evidence and we’re actually just waiting to publish a new to yesterday that we’ve done ourselves and increase adherence to dietary change when you have genetic data with us. So that kind of makes sense. I mean, you understand more about the why behind giving some advice rather than just following, let’s say, a mainstream sort of commercial branded diet, if you will. So you sort of make your own decisions based on not just a prescriptive meal plan, but actually on how you’re made, right? So that kind of improves that, but some of the really interesting things and things that our customers love, right?

24:43 I mean, what people don’t realize is like, let’s say lactose tolerance, so ability to digest milk as an adult is called lactose tolerance or in the sort of more specific things, is the lactase persistence.

24:56 So there’s an enzyme called lactase which helps break down lactose, which is the sugar in milk. Right? And if you are born in the UK or Australia or North America or maybe South Africa, you probably think it’s entirely normal to drink milk as an adult and you have no problems with it. If you’re born in East Asia, for example, you probably don’t. And that’s because there’s a genetic mutation that occurred some point between sort of five to 3,000 years ago in central Northern Europe and spread, which allowed people with this variant to digest milk as adults. So to create that enzyme, lactase as adults. In most people, it turns off at the early life. So I see about 65 somewhere to 70% of the world are actually lactose intolerant, but we consider it more normal if depending on where you’re born to be like, “Oh, yeah, yeah, of course, I can eat milk or yeah, I can eat dairy or milk as an adult.”

25:53 So basically it’s really interesting because sometimes people are so surprised actually. Yeah. I mean, [inaudible 00:25:59] says, “I’ve got this gene, which means that actually I’m not generating lactase, so when I do drink milk I’m a bit bloated. I do feel a bit uncomfortable there.” That’s because the way they digest lactose has to go through a secondary pathway, if you will, as opposed to the primary one using basically your genes are using the enzyme in the most efficient way. So yeah, it’s really interesting, so small, but it actually tells you something about your ancestral heritage as well, which I find really interesting.

Stu

26:29 Yeah. I know, it’s fascinating stuff. And I’m just thinking about epigenetics and I’ve had a few conversations with some guys on here about how we can change certain genes over time with diet and lifestyle. Do you recommend re-testing after any period of time to accommodate perhaps a change that may occur in our genes?

Andrew

26:50 No. So what will you report on is called your genotype and that will never change regardless of what you do and how you use that data, of course will change. So let’s say, for example, that a good example of epigenetics would be that ACT and 3′ gene, let’s say, right? So that I mentioned which was the [inaudible 00:27:09] gene. So there’s basically by doing something in combination with that genotype … Oh, my lights has gone off in this office? One sec. Let me just move back on. Give me two secs.

Stu

27:24 [crosstalk 00:27:24] There we go. Back on.

Andrew

27:35 All right.

Stu

27:36 Fantastic.

Andrew

27:36 So where did we stop? Epigenetics.

Stu

27:38 Yes.

Andrew

27:40 Okay. So yeah, basically your genotype will never change from the moment you’re conceived to the moment your last cell decays away into the earth, you will have the same genetic genotype all the way through that journey, right? What you can do is change the activity of a gene with certain lifestyle changes.

28:03 So if we use the ACT and 3′ gene, which we talked about in terms of sprint response before, then that’s quite a good example. So let’s say, if you’ve got that C-version of that ACT and 3′ gene, that’s the one which is associated with being an olympic sprinter response, should we say, and it’s not going to build faster as most of the fibers if you don’t give it any exercise on as a default. What you do in your environment has the cause that gene to express and take its activity. And so why we effectively do here is by understanding this, we hopefully tweak your lifestyle and your environment to get the best effect from what you have and almost express those barriers that you might have with the optimal kind of lifestyle change.

28:53 So we cannot change what genes we have. That is not what epigenetics is about. Epigenetics is about how can we make those genes express or be active in the best way possible? And that’s where this interaction between genes and environment come in.

Stu

29:08 Got it, got it. Okay. Now, yeah, that’s a valid point. I think there’s a little bit of confusion around how this interaction occurs and whether we should be a little bit more vigilant in what we’re doing in terms of things that we can change or not.

29:26 So there is a gene that I’m familiar with which is the MTHFR gene and it gets lots of press over here about it and what it can do. Is that something that you guys interact with and can you explain what it is to our audience as well?

Andrew

29:45 That’s right. Yeah. So let’s think of the word gene as a segment on your genome. Right? And within that gene there are certain different locations, specific locations in that gene which are called SNPs, Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms. And so MTHFR has been quite well talked about, right? I mean, it is long name somehow isn’t quite as catchy, sort of methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase, I believe is the long name. And is basically it’s part of like a chemical pathway called the methyl cycle. And the role of this is to convert homocysteine to something called methionine.

30:31 So there’s two locations in this MTHFR gene, which we talk about, the two SNPs, if you will, and we test for one of those SNPs and not for the other. And so we test for certain SNPs, which is if people want to know it’s called C677T. And this has a consensus about activity. So let me give you an example here, right?

30:55 So again, with this gene, you can have one of these three genotypes, two copies of the C, two copies of the T or one of each. So CC, CT, or TT, right? Basically, if you’ve got the CC genotype, the enzyme works quite well. It does its job quite well. However, so it’s very efficient basically. It’s producing, it sounds quite well. If you’ve got the CT genotype, so one of those Ts, it’s about 80% as efficient. So it’s a little bit less efficient than those with CC. And then if you’ve got two copies of the T, the activity of this enzyme is quite significantly reduced. So it’s about as low as about 35% of that efficiency.

31:38 And if it doesn’t work well when I say, it’s not as efficient, and you’re basically not as good at converting that homocysteine to methionine, which basically means you could have a build-up of homocysteine in your blood. That has been linked, so there’s a potential sort of health detriment to having sort of consistent excess build-up of homocysteine in the blood, and that’s linked to a certain longer —

32:00 … cysteine in the blood and that’s linked to certain longer-term, lifestyle health disease stuff, so around cardiovascular disease, hypertension, et cetera. But homocysteine is very easily reduced with the B vitamins, so B6, B9 and B12. So basically, what we do is we report on this particular SNP and we say, “Well if people have the T genotype, the T allele, of the MTHFR gene and this SNP or the TT allele’s there, then we want them to get a little bit more of these B vitamins in their diet”

32:32 And there’s been some good studies there showing that, if people had, let’s say 600 units of vitamin B9 in their diet compared to the RDA which is 400. Then that was … they have a good effect on reducing the homocysteine. Now, the controversy comes in, a lot of people, maybe your listeners or yourself, have come across the other SNP in the MTHFR gene right?

Stu

32:53 Right.

Andrew

32:55 And there’s an opinion out there that this is, depending on the version of this [inaudible 00:33:02], it could be responsible for a host of other illnesses and diseases, and actually the evidence doesn’t really support it. There’s not a consensus of evidence. One of the factors that we say is for every single SNP we report in our report in our products, we have to have a consensus of its effects on humans with a modifiable lifestyle environment change.

33:21 So, some people believe that if you’ve got a certain version of MTHFR that you can’t take a certain supplement and that increases risk of some pretty serious health impacts and so on. The evidence is not really there, especially not in a consensus that we feel comfortable to communicate that. So we stick to this other SNP, which does show if you’ve got this version, aim for more of these B vitamins and you can bring down your homocysteine levels. So, it’s not as scary as maybe some people think. And I guess that might be what you’ve come across, is that right? Sort of this-

Stu

33:55 Yes. Yeah, it is. They’re almost painting it with this picture of “Oh crickey, you know, I hope you haven’t got this gene because you’re doomed.” But that explantation painted the perfect picture, so thank you.

Andrew

34:06 And a lot of the time is that, I think due to pop culture, like Aldous Huxley and that film Gatttaca, people tend to think of DNA as deterministic of what you will or won’t be, have some bad news, et cetera. But all it ever does is increase or decrease a certain likelihood or predisposition of something, if the environment is also the same, right?

Stu

34:31 Right.

Andrew

34:32 So, always the best way to think of this is, it is not destiny, it’s only opportunity to make changes that you can then support or cancel out a certain genetic activity. So we just do this in a very- it’s a very conservative measure, it’s at one factor, your DNA is not everything, it’s just one part of the picture. And just as you wouldn’t rush to make an entire lifestyle change based on a single heart rate result or a single other measure that we are used to, you shouldn’t do that for your DNA data either. It needs to be so measured, so conservative, but it can give you that underpinning of understanding where you should be aiming and how you’re made, to influence a lot of your other decisions too.

Stu:

35:14 Got it. Got it, excellent. If I order the kit, what are the requirements before I take the swab? Is it like, for instance, giving blood? When they recommend that don’t go to the gym and lift heavy weights before because you might increase inflammatory markers, things like that. Do I need to be aware of th-

Andrew

35:33 No, no. The only thing we really say is ideally you won’t have eaten or drunk anything other than water in maybe the previous 30-60 minutes. And the reason being, let’s say you’ve eaten a load of beef before you do the test, they’ll be elements of beef DNA in the sample, right?

Stu

35:51 Right.

Andrew

35:53 So we just ask that so we get a nice, clear sample and we can extract the human DNA that we need to.

Stu

35:58 Perfect, okay. So I’m just trying to think, so people that are gonna be really well versed to the information that this testing offers will be, pretty much everybody … It’s gonna help with potentially weight management, that would be right, wouldn’t it?

Andrew

36:20 That’s right.

Stu

36:20 Energy as well. So if I’ve got low energy, there’ll be a … should share some clues as to what’s going on there as well. What about sleep? What about if I’m a terrible sleeper? Will that offer me any insights into perhaps what I could do to improve my sleep?

Andrew

36:40 So, you’re a slow metabolizer of caffeine in your CYP1A2 gene and you have a, let’s say, slightly above the average consumption of caffeine, that will definitely have a certain, larger impact on your sleep. There’s another gene actually called the ADORA2 which plays a role there too in insomnia risk in caffeine consumption. But there is actually genetic factors around sleep as well, which we’ve just built a new product, it’s not quite on sale yet but we’re putting that on soon, around sleep and stress. And so, there’s genetic components to, what we call, your chronotype, right? So whether you’re more predisposed to be a lark, an early bird or a night owl. And there’s a genetic factor to that, around your circadian rhythms.

37:23 There’s a genetic factor to your likelihood of deeper sleep than average or not and also under average duration of your sleep as well. And if you think about all these lifestyle things, we know if we all hang out in a group, that people are individual even when the environment is the same. And when the environment is the same but the outcome is different, you have to look for a genetic factor because everything else is the same, and they’ve done this through twin studies for example. If you put the same impetus in but you get a different outcome, then there’s probably something happening in the engine in the middle and that’s the genetic part of it. So, basically yes, sleep, stress response, nutrition response, exercise response, these are the areas of health and well-being that we’re interested in and that’s what we provide in our products basically.

38:10 So yeah, sleep is a really interesting one. Like I’m a genetic night owl so it’s okay, it’s 9PM here in the UK and I’m doing this podcast. And I do, I feel better later in the day, I can concentrate better, I feel like I’m actually working more efficiently, if you will, at this time of the day.

Stu

38:28 That’s interesting. And I’m the complete other end of the spectrum. I start to fade … if I’m not in bed by 10:30 then the next day doesn’t work out well for me.

Andrew

38:38 And look, it’s not all the genetic, right? There’s obviously so many elements, the training et cetera but the funny thing is, even when you do huge meta analyses on identical twin studies that grew up in different environments, et cetera, is most things end up around 50/50 between DNA and environment. And so even when certain traits … there’ll be much more of a factor that’s genetics and traits that will be much less of that factor that’s made of a genetic variant. But when they actually do a massive, sort of overall view, we tend to get to around half and half.

39:12 And so, okay it’s not gonna be genetically everything, the fact that you feel better in the morning but there’s probably a factor there that underpins that. And so, there’s no bad news. There’s only just finding out more about yourself so you can make a better personalized tweak basically.

Stu

39:27 Perfect. So what about the future? I’m excited to hear about the sleep and stress product that you guys have in the pipeline, I think that will be invaluable, certainly to me that’s for sure. But what does the future hold for personalized DNA, from your end?

Andrew

39:48 So I think on the big, sort of a global picture, I really believe that some point soon we will probably all own our own genetic data from birth and keep that somewhere to be accessible. So a raw data file of how we’re born, our genetic code, will probably at some point be on our smartphone and we can do with that what we wish. So now at this moment, you have to buy a test, do the swab, send it off to the lab, et cetera. I believe soon that that will just happen automatically at a certain point in our life via our health systems and we’ll know that data and we can use that data ongoing for the rest of our life.

40:22 So it’s happened with … the UK did a big 100,000 gene S project which just concluded recently and was very positive. The country of Estonia are attempting to get a point where they might genotype their entire population. So there’s a big change in that and it’s about the cost of sequencing is coming down so much that we can do whole genome sequencing for an entire population in near future. So it’s crazy.

40:45 For us, what I’m really interested in doing is closing this loop. So we have this static part of our environment, our health, which is this genetic part and let’s say we’re staying at this wellness end of the spectrum, we say, “Hey, here’s the genetic factors, here’s your health coach, make some decisions based on that.” But what we don’t currently have done is actually we’ve not really measured the other parts of that environment. So the other variables.

41:11 What we’ve just done is we’ve just launched our first beta program of an at-home blood test called SnapShot where we’re looking at blood biomarkers to get a realtime snapshot of your current status of health, especially in biomarkers related to their genetic factors which are reported in the report. And we actually have the first every system, as far as I know, that looks at genetic interactions in a blood profile. And we’re doing that, again, from a sort of beautiful user experience. And then we want to really try and take that to the next stage and say, “Okay, well how can we then provide you some personalized supplements or other personalized foods actually delivered to you, for example, that take into account both where you’re at right now and how you’re born and that genetic profile affects.”

41:56 So we can sort of start to really create this personalization ecosystem and build on it as we go. It might be integrating your variables, it might be integrating your scales, your heart rate, it might be integrating all the activity you’ve just posted onto your social media, right? So, I want to get to this point where suddenly we can be an engine that makes sense of all this data for you, individually, in a sort of usable, beautiful, actionable way.

Stu

42:23 Fantastic. Boy oh boy, it’s exciting stuff, isn’t it? Radically changes the way-

Andrew

42:31 Yeah, we try.

Stu

42:32 Very intrigued just to learn so much more about this because it’s these tiny little tweaks that we can make to our diet, lifestyle, health, all of the above, that just radically change the way we feel. And yeah, very exciting stuff. So-

Andrew

42:47 The way I always look at it is like, something may seem like a small tweak on its own but cumulatively that leads to a big change. And just stars in elite sport … it wasn’t like I just did one, huge session and that made me an Olympic athlete, it was a lifetime of working on these things and improving small amounts over a cumulative, long-term approach. And I think, even something as small as, “Okay, I’m gonna reduce my caffeine content by this amount per day because I know now that, genetically speaking, I’m a slow metabolizer of caffeine.” That has a longer-term health benefit than if you didn’t know that at all.

Andrew

43:23 So we’re just trying to improve on the public health guidelines with a bit more personalized data.

Stu

43:28 Love it, love it. So we’re just about coming up on time but I have a question that I ask everybody towards the end of the show, and that is, given everything that you know and all of the information that you’ve accrued over time, what are your non-negotiables to ensure that you crush each and every day? So it might be the small little habits that you know that you have to do every day to be on top of your game.

Andrew

43:53 So I think, as an athlete, I spent my entire life training outdoors no matter what the weather, whether I was in the desert in Arizona, whether I was in … I spent a lot of time the AIS in Canberra, whether I was in the rainy North of England. And so I always make sure I’m outdoors for a period of the day no matter what. So here in London that means quite a long walk to work, I live relatively far from the office but I often try and walk no matter the weather or what. I try and get that natural light to get my sort of certain circadian rhythms working properly and let me focus. So, I always make that happen no matter what and I think too often in everyday lives with offices and the stress of work especially in a city where you would probably drive to this office et cetera, people really don’t get outdoors enough. And that gets you vitamin D, it gets you all sorts of other benefits too so that I always get everyday.

44:52 And the other thing was I always get, for better or worse, is probably too much coffee. That’s a non-negotiable for me as well is that I drink a lot of coffee and I try to drink good quality coffee at that.

Stu: 45:05 Brilliant, fantastic. So what’s next for Andrew Steele and DNAFit? What do you guys got in the pipeline?

45:14 So we’re really working on just trying to grow the understanding of the need for personalization. So we’ve got some really exciting announcements coming up around a bit more of an international expansion. We were actually acquired by a group earlier this years which gives us the scale to really have a true global footprint. And then I’m really excited about our products developments, which is what I mentioned around this blood testing product, the supplementation for example, and how we can make this overall personalized ecosystem.

45:49 So for us and for me, that’s exactly what we’re aiming towards. And it’s, like you said, a really exciting area and I think it’s something that which is only gonna grow, especially as the understanding of DNA data and the prevalence of genomic sequencing increases.

Stu

46:07 Yeah, definitely, this stuff is not going away that’s for sure.

Andrew

46:12 Yeah, 100%.

Stu

46:13 And where can we send our audience? They wanna find out more about you, about DNAFit, order a kit, or just find out everything about this service?

Andrew

46:21 Sure yeah, so for DNAFit just head over to our website dnafit.com, we got everything about the products itself there. If you wanna get in touch with me directly, you can just find me on social media, my handle’s just andrewsteele, all one word. So there get me there on Twitter or Instagram et cetera and you’ll find me posting about all things sport and all things sort of health, wellness, and genetics as well.

Stu

46:48 Brilliant, thank you mate. Well I will share everything that we’ve spoken about today, including all the links to the sites and the locations in the show notes. But thank you so much for your time, especially at this ungodly hour for me at least. And we look forward to following your journey in the future, so thanks again.

Andrew

47:08 Cheers to you, thank you so much.

Stu

47:10 Okay, thank you mate, bye bye.